|

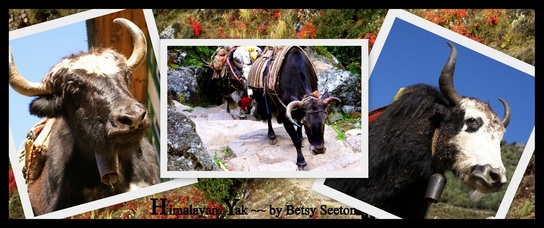

Known to some as jewels that grant all your wishes (Tibetan interpretation) the yaks pictured here live in the Himalayan region on the Nepal side and can trek as high as 20,000 feet; higher than almost any other animal on earth. These large beasts, weighing up to 1,800 pounds (I've read even 2,200 but not sure that's true), are well adapted to high altitude because their red blood cells hold three times the oxygen of other like size animals. Most yak stay above 12,000 feet elevation their whole lives and do not usually survive below 10,500 feet. While there are 12 - 14 million domesticated yak in the world, there are only an estimated 2000 or fewer wild yak (aka Drongs) left on the planet. China has listed the wild yak as one their officially protected animals. Males of the species are technically called Yak while the female is referred to as Nak or Dri. Whether female or male, however, to most non-locals the world over, Yak is the commonly used term encompassing both sexes. Most of what trekkers in the Himalayans come in contact with are Dzo, which is a crossbreed of a wild yak and a cow. Again,the term Dzo is technically the male of the species and females are known as Dzomoor or Zhom. Below are pictures of the Himalayan terrain as we headed toward Mt. Everest. In this article, you'll also find pictures of yaks along the trails and pictures of Sherpas and locals with their back breaking loads. All photos are for sale directly through me or through my online art gallery. Yaks are some of the most, if not the most, sure footed animals you'll ever see. They can carry up to 210 lbs while traversing over suspension bridges and up and down narrow, rocky paths. It was remarkable watching them negotiate the terrain, fully loaded down with heavy, bulky packs and not once seeing them slip or falter. One of the rules of trekking was to always give yaks the right of way on the trails. Human trekkers were to step aside and always, always yield to the yaks. Sometimes that meant standing on the outside of the path's edge with nothing between you and a thousand foot drop off.  A REAL TREKKER - by Betsy Seeton A REAL TREKKER - by Betsy Seeton This is one of my favorite pictures I took on the trek. The elevation here was about 14,000 feet. The hardy woman was trekking between villages. Much of what is brought into the small villages is packed on the backs of humans or animals. Below are pictures of Sherpas and locals -- common examples of what was typical to see along the trails.I was continually amazed at the strength and endurance of the locals ....  Yak herder searching for more rocks to throw at her yaks - by Betsy Seeton Yak herder searching for more rocks to throw at her yaks - by Betsy Seeton Here the yak herder is looking for more 'encouragement' to throw at her yaks. Yaks often walked single file, but the rocks flying at them riled this group and caused some commotion.  Yak and herder on the Everest trek in Nepal -- by Betsy Seeton Yak and herder on the Everest trek in Nepal -- by Betsy Seeton One independent yak was not happy with this herder's flying rocks ..... Yaks can live up to the age of 25 and are the lifeblood of the Himalayan people. They provide food: meat, milk, butter and cheese. Their fur and hair generate a steady stream of income as its made into cashmere blankets and sweaters. It's also used for tent material, purses, bags and even made into rope. The undercoat and hump hair is made into cloth. Sometimes the tails are sold as fly swatters.  Yak dung drying out - by Betsy Seeton Yak dung drying out - by Betsy Seeton On my trek to the base camp of Mt. Everest in the fall of 2006, our group stayed at various tea houses along the trail. In the evenings, the wood stoves would get stoked up with piles of dried dung, burned much the way westerners use firewood. Once the stoves were roaring hot, pans of water were heated for showering. The hot water was poured into containers perched above our make shift outdoor shower stall. There was enough warm water to very quickly wash as long as you turned the water on and off while soaping up and rinsing off.  by Betsy Seeton by Betsy Seeton Dried yak dung is a large source of what locals in the Himalayas use for heating and cooking. It was common to see yak dung made into paddies and dried on the side of dwellings like you see in these photos. An estimated 7,000 of these paddies will heat one home for through the long, harsh winters.  Yak meat being packed up the Everest trail - by Betsy Seeton Yak meat being packed up the Everest trail - by Betsy Seeton This is how yak meat was packed up the trail to the various tea houses. It was out in the hot sun for hours. After seeing this, most trekkers were happy to order vegetarian only dishes.  by Betsy Seeton by Betsy Seeton These were the long haired yaks on the last day of the trek to the base camp. This photo was taken at over 17,000 feet elevation.  by Betsy Seeton by Betsy Seeton Yaks getting to rest between their trek to the next village on the Nepal side of the Himalayas. Below are more yak pictures. The airplane photo was on the October morning we flew into Lukla, Nepal where we started our trek. The first village we spent the night at was Namche Bazaare. It's an historic trading post where Nepalese and Tibetan traders exchange salt, dried meat, gold and textiles. The following morning, I was outside our tea house brushing my teeth alongside our porters (what many people call Sherpas). I felt something at my back and when I turned around I found myself face-to-face with a very large yak! The first thought that went through my mind was how my daughter would have loved that. She is an animal lover like I am, starting from the time she was a toddler. It was one of those extraordinary moments that only traveling to far away places can ever bring. I only wish someone would have caught the moment on film! I'm sure my expression was priceless!  Rocky terrain toward base camp - by Betsy Seeton Rocky terrain toward base camp - by Betsy Seeton To say yaks are the "lifeblood" of the Himalayan people also has a literal interpretation. Some Tibetans and Nepalis drink cups of yak blood in the belief that it will cure all kinds of diseases. It's also used as an aphrodisiac. There's a controversial festival in Nepal where yaks are drained of their blood for human consumption. The article below from thehindu.com explains more: STRAIGHT FROM THEHINDU.COM: Men, women and even children have been heading for Myagdi, a remote district in western Nepal, to take part in the khun khane ritual, which literally means drinking blood. The festival sees the local yak herders making money by selling the blood of live yaks to people who queue up in hundreds to drink it, in the belief their illnesses will be cured. While lactating female yaks are spared, other yaks above the age of two are chosen for the ritual. Pinned down by people who hold their tails and horns and their legs tied, the yaks are then bled by a professional bleeder, known as the aamji. The aamji pierces the jugular vein of the hapless animal and the streaming blood is collected in cups that are then passed among the crowd, who drink the warm, frothy liquid unwaveringly. Each yak is bled to collect between 20 to 40 cups of blood. The ritual is believed to be an old Tibetan one that originated in Mustang in northern Nepal, once part of an ancient Tibetan kingdom. The participants are mostly people suffering from chronic diseases who have given up hope of being cured by modern medicine. An American researcher, Zorina Curry, who studied the khun khane festival, correlates the ritual to the belief in witchcraft and the superstition that blood is effective as medicine as well as an aphrodisiac. However, Curry also warned that since the yaks were not inoculated, some had TB and the blood—drinking could infect the human drinker. The festival has been condemned by Nepal’s animal rights activists who last year urged the government to stop the slaughter of tens of thousands of animals and birds at the five—yearly Gadhimai Festival but to no avail. The Animal Welfare Network Nepal (AWNN) has termed the khun khane practice barbaric. “Can you think how painful it must be for these innocent creatures to have their necks and bodies pierced and to be drained of blood?” AWNN had said in an earlier statement. “Humanity as a whole must speak out against cruelty against living beings in the name of religion, culture or health.” RAISING YAKS FOR FIBER  FROM YAMPA VALLEY YAKS FROM YAMPA VALLEY YAKS I found several yak ranches in Colorado where yaks are bred for meat, dairy, fiber, and as pack animals. I came across this interesting article on yak fiber too. Below is part of the article straight from the website of YAMPA VALLEY YAKS located near Steamboat Springs: Yaks produce two types of hair. The outer coarse guard hair is good for braiding into ropes and halters or weaving into rugs, belts, and bags. The soft underhair is called "down" and has a diameter of 14-16 microns, comparable to cashmere. For maximum softness, it must be "dehaired" to remove any guard hair. It's very short staple make it a challenge to spin in pure form and it is often blended with fibers with a longer staple such as wool or silk. Yaks living in cold weather will put on a heavy coat and produce one to two pounds of fiber annually. If you are considering a yak for fiber production, the first and most important thing is to have tame yaks, ones you can handle easily. Then it is a simple and enjoyable task to groom them in the spring to collect the fiber. Since we have royals, I try to comb out the fiber by color and keep one bag for white, one bag for black, and one bag for mixed. I wash each batch by soaking it in hot water and detergent in the automatic washer. DO NOT agitate it or you will have a washer full of felt. After it is dried on a screen, I send the down off to Canada to be dehaired. Unfortunately, the dehairing process for cashmere will not work on yak, as yak has several intermediate lengths of guard hair. Minimills in Canada is the only place I have found to process so it adds considerable cost to the price of yak down. The down then needs to be carded very carefully (or not at all). I spin it "softly" and knit natural -colored sweaters and caps with it. For easier spinning, it can be blended with other fibers. Lambspun in Fort Collins, Colorado, blends a yarn of imported yak, wool, and silk to make a beautiful and prize-winning yarn. READ FULL ARTICLE HERE ARE A FEW WEBSITES WITH INFORMATION ABOUT YAKS

(I cannot attest to the accuracy of the info found at these sites.)

1 Comment

Chris Smith

3/25/2012 02:16:54

Wonderful story Betsy....

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

"Ask not what an animal can do for you; ask what you can do for an animal." Jasper

"The animals of the world exist for their own reasons. They were not made for humans any more than black people were made for white, or women created for men." ~Alice Walker The source of the quote is Walker's preface to Marjorie Spiegel's 1988 book, "The Dreaded Comparison" . Her next sentence was, "This is the gist of Ms. Spiegel's cogent, humane and astute argument, and it is sound." Archives

February 2015

"I was so moved by the intelligence, sense of fun and personalities of the animals I worked with on (the movie) Babe that by the end of the film I was a vegetarian." ~ James Cromwell Categories

All

|